Autopsy Case Files

(Quick disclaimer: this is in no way meant to be gross or disrespectful. The class and the…

(Quick disclaimer: this is in no way meant to be gross or disrespectful. The class and the entire university places immense importance on teaching by seeing/doing, and they take it very seriously. There is absolutely no giggling, ogling, or any kind of disrespectful behavior, so please don’t think that. We all understand the honor of being able to pay testimony to the patient’s last moments, and we are all grateful for this opportunity.

Also, I am not a pathologist; simply a student, and I’m learning. Mistakes may be made, and I recall the details of the cases from memory, so if you find any errors, please let me know!)

Warning: pictures are included, which may or may not bother you if you dislike images of organs and body parts. Please tread carefully!

Nov, 2018:

Today we saw a unique case; unique because I hadn’t seen one before, not because the case is so rare. The elderly male patient presented to the hospital with chest pain and was treated for his cardiac insufficiency, on the suspicion of

amyloidosisin the background. Since he had a history of

multiple myeloma, the suspicion made sense. Despite treatment, the man passed away from heart failure and arrived to pathology.

A few quick words about MM and amyloidosis: there are many different types of amyloidosis, but the one associated with myeloma is called systemic or AL amyloidosis, and is due to the accumulation of immunoglobulin λ,κ light chains derived from the increased number of plasma cells.

Can you tell which one is affected and which is from a healthy heart?

Amyloidosis is extra-cellular accumulation of these proteins, and can be seen microscopically with Congo Red staining. But there’s also a way to test for it macroscopically in the autopsy room! It’s a bit historical, but our prof was nice enough to show us the

IODINE-SULPHURIC ACIDreaction: first, drop a bit of the affected tissue (in our case, the myocardium) into iodine solution, and let it soak. Then carefully transfer it to a dish filled with sulphuric acid and wait. You should observe that the affected tissue turns BLACK or very dark brown, whereas healthy heart tissue is just slightly tinted by the iodine solution.

The rest of the autopsy was focused on the

HEART, which was even macroscopically different than a normal heart. Not only was the heart muscle hypertrophized, but its consistency was different — it felt waxy, almost like touching bacon fat. Clearly a heart that could not contract sufficiently; look at how thick the walls of the heart are, and how small the ventricle lumen is.

And finally, the patient had an incidental finding; not actually dangerous — more of a curiosity. If you’ve used Pathoma to study for patho, you’ll know that anemic infarcts often leave a triangular area of whitened tissue — and we had a spleen that portrayed that PERFECTLY. Check out this beautiful specimen of a (chronic) anemic infarct: an artist couldn’t have drawn it more triangular.

Nov, 2018:

This case was a really really difficult one, and for obvious reasons I decided not to attach photos. The patient on our autopsy table was a neonate, who had lived for only 55 hours after being born via C-section, prematurely. I don’t want to discuss the specific case, but I thought it might be helpful to discuss how a neo’s autopsy differs from an adult’s. (Note: I’m not a pathologist, this is just based on what I noticed that the prof did differently. I did look up perinatal autopsies and used that as reference, though.)

- NEC (nectrotizing entercolitis) — the bowels are checked to make sure that there isn’t a portion that has died. The exact cause of NEC is unknown but is thought to be multifactorial, and it is most often seen in premature babies. Our patient did not have NEC, but I included a picture from Robbin’s for reference.

- heart: check for congenital anomalies! Use that embryology knowledge to verify that there were no abnormalities of the infant’s anatomy.

- lung float test — another historical test; this isn’t used anymore because of controversial results, but it was used infrequently in the past in cases of suspected infanticide. You simply place a small piece of the infant’s lung into a dish of water, and if it sinks, then it wasn’t full of air (which made investigators in the past believe that the child never had the chance to respire). However, lots of things can cause false negatives and positives; for example, we knew our patient had been ventilated before her death, but the lung did drop directly to the bottom of the water dish.

March, 2018: Last week’s autopsy class was so uninteresting that I was hesitant, not looking forward to what this week would hold. I really didn’t want to stand through another 90 minutes of repeating the same common findings, but as it happened, that wasn’t the case.

My teacher is a really enthusiastic young man with a love of teaching and a penchant for finding (and keeping 😉) the most interesting cases for us. So today when he announced we’d have three cases, I was excited.The first was by far the most unusual.

So, the first case. At first glance, it seemed like he had heart cancer. You don’t hear a lot about cardiac cancers, and that’s because it’s very rare. As it turned out, this wasn’t what happened here either. It was instead a lung cancer, so sneaky and aggressive that it invaded the right atrium. The tumor further eroded the pulmonary artery, which was the ultimate cause of death.

You can see the forceps pointing at the tumor that invaded the heart.

The second case was a dilated cardiomyopathy, which, unfortunately, is a common diagnosis in the country where I study. What was interesting (and quite sad) was the intense autolysis, which made the organs look really different.

The third case was perhaps the most shocking, something I’d thought only happened in television shows. The poor gentleman had had gangrene of the lower limbs that was more severe than what I could’ve imagined seeing in a pathology class, and we spent a long time discussing his story.

Severe gangrene of the lower limbs in a patient that likely lived alone.

I write this more as a journal entry, one of a naive, impressionable, curious medical student, sharing her experiences. My primary aim is to learn from all we see, and use it in my future career.

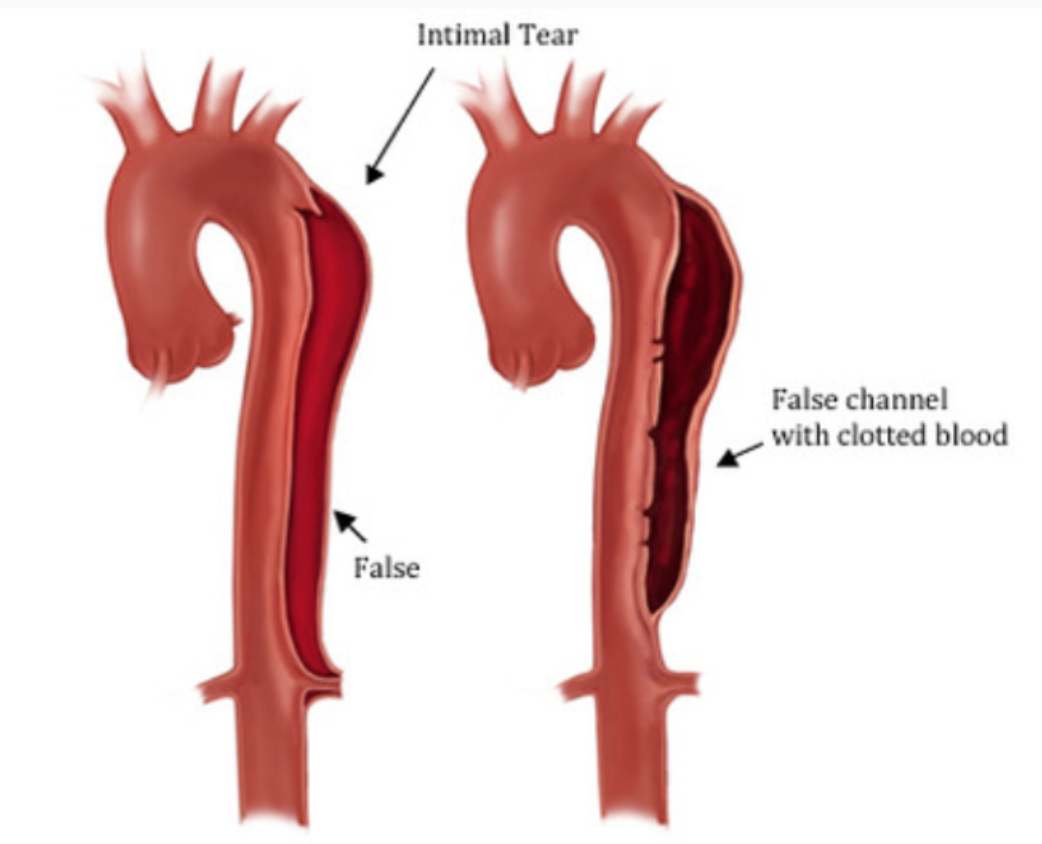

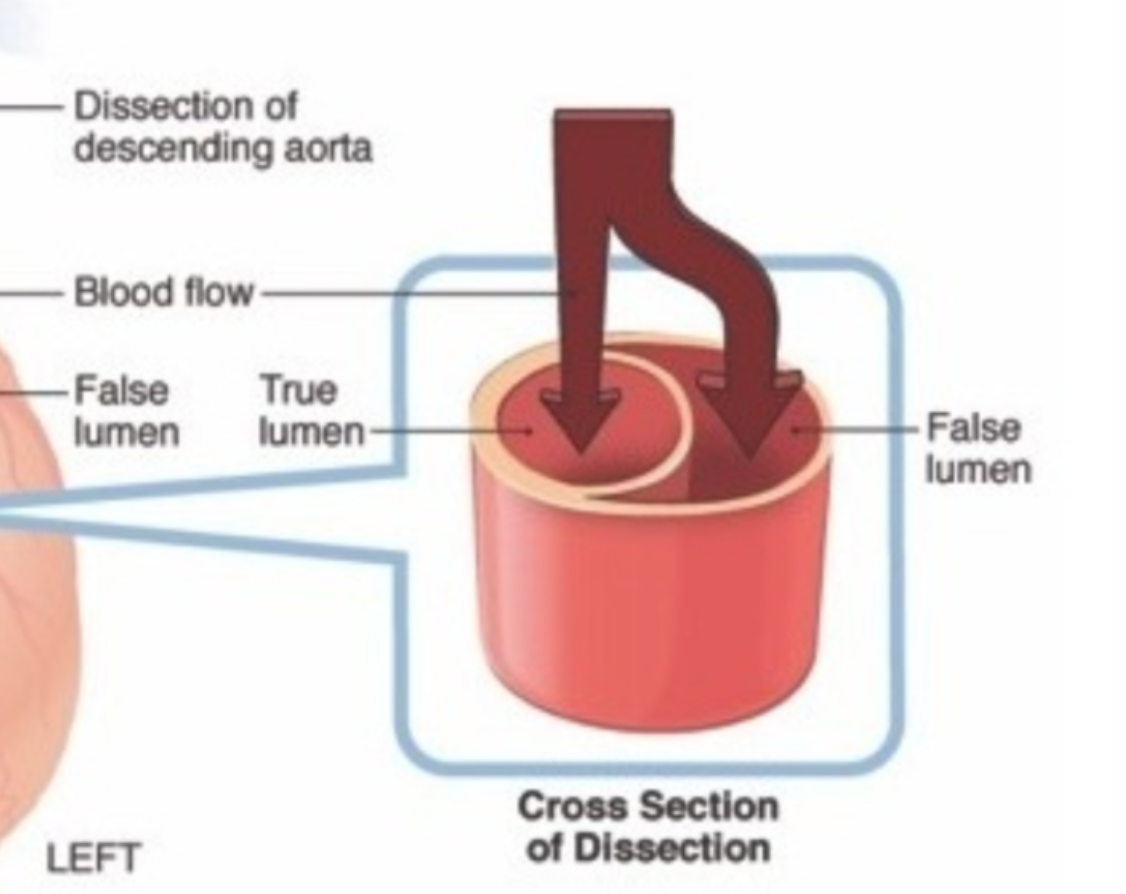

My classmates and I gathered around a 54-year old lady who was seen to have an incredibly dissected aorta. I had never seen one this severe – the walls were hard, calcified, and the false lumen was thicker than the aorta, like a metal pipe compressing the true vessel into a tiny little slit (see the picture below). But what really struck us was her medical history. They had found her dissecting aorta 6 years prior, but the patient had refused surgery. All of us became silent as we thought about why a patient would refuse a life-saving surgery. It seems to happen all the time, and we, young, naïve medical students, can’t help but wonder, “But…why?”

Aortic dissections occur when the innermost layer of the blood vessel tears a bit, and the blood can now flow between the layers of the vessel. Sometimes there is an exit tear at the end of the false lumen, which allows the blood in the false lumen to flow out, back into the aorta. This was the case for our patient, who she was lucky to have lived 6 years after her diagnosis. This was because the false lumen had filled with congealed blood and eventually blocked this second lumen, restoring blood flow to a kind of normalcy. But at the place where the false lumen ended, the flow was turbulent. This resulted in the formation of a complicated plaque that with time weakened the wall of the aorta and lead to a massive rupture, causing blood to pour into her abdominal cavity and ultimately, death.

It’s impossible to know what the patient had been feeling at the time of her diagnosis. We have no idea why she’d refused the surgery, but our professor surmised that fear had likely been a factor. A lot of the patients, he says, especially those from the countryside, are terrified of surgery of any kind. We can only imagine that her physician tried to talk her into it but she likely didn’t budge. And then that’s that: we have to respect the patient’s wishes, difficult as it may be to bear. It’s going to be tough.

P.S. There was an incidental finding: the patient had a meningioma, a benign growth in her brain that was undiagnosed. You can see it as a firm, oval-shaped bulge in the upper right-hand corner of the photograph.

How an aortic dissection looks. You can imagine how clotting might actually save the patient's life.

A close-up of the false lumen.

A meningioma, which is a benign tumor of the brain and an incidental finding in this case. It's the white-ish round glob in the upper-right hand part of the brain.

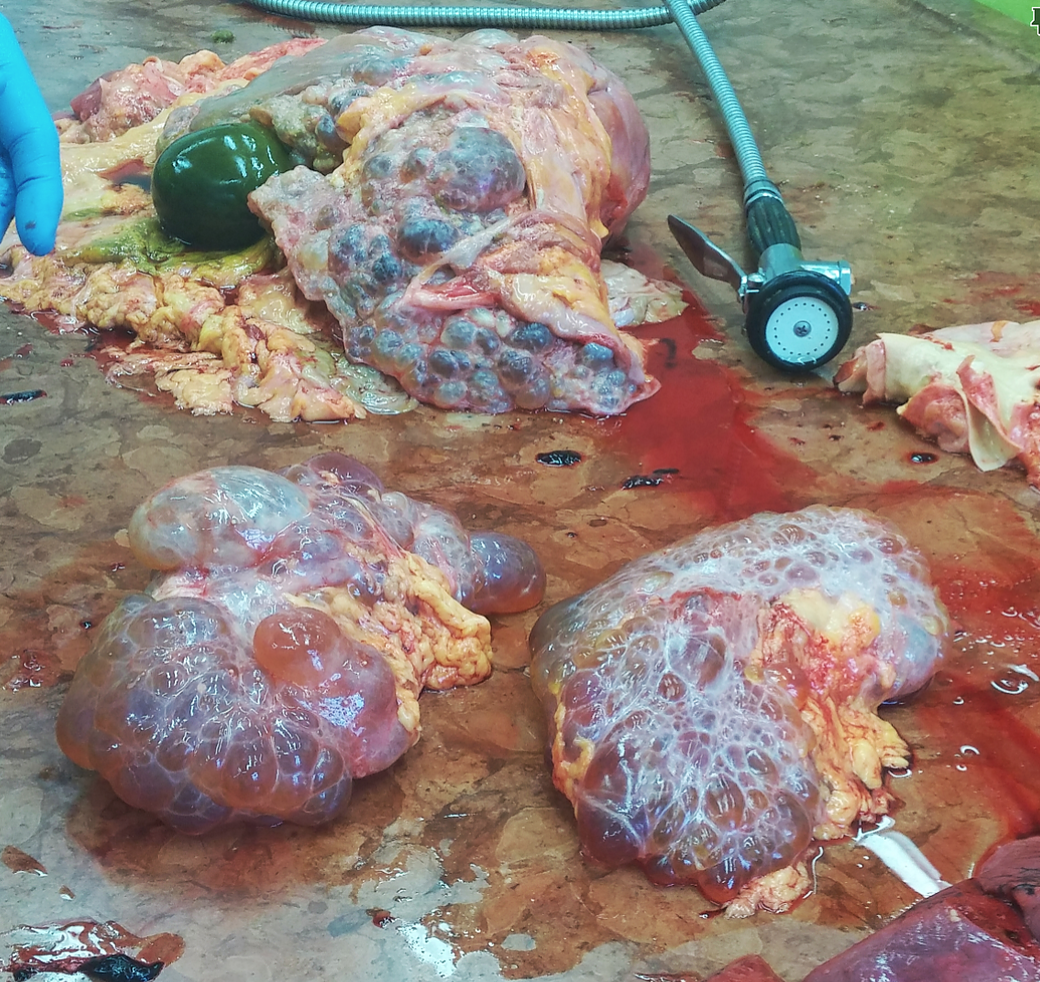

Last week’s autopsy case: a 74 year old woman who had died of complications of her polycystic kidney disease (PCKD), which is a genetic disorder of the autosomal dominant type. She had had a kidney transplant over 20 years ago and the new kidney served her well, until she got an infection that couldn’t be contained.

As class ended, my prof told our other teacher to be sure that they speak with the family about screening for the genetic disease, at which point I said to him, “But she was diagnosed over 20 years ago; surely someone along the line had thought to screen her family, no?” To which he replied, “Yes, we hope. But in case our colleagues haven’t…” And THAT right there: that is the kind of doctor I want to be.

The case was very unique because (apparently) neither of our teachers had ever seen the involvement o the small intestine. They wanted to ask about preserving it as a specimen for future classes, but if not, then the professor assured us that photos of it would be featured in next year’s pathology lectures.

The outside of the two kidneys.

The cut surface of the kidney, showing the fluid inside the cysts.

Polycystic liver involvement.

Involvement of the intestines! Unexpected; our professors actually took a picture of it.